Ethical dilemmas in technology and innovation

Overview of Ethical Dilemmas in Technology and Innovation

What constitutes an ethical dilemma in tech?

An ethical dilemma in technology arises when competing values collide and there is no clear right or wrong choice. Design decisions may promise significant benefits yet carry potential harms for privacy, autonomy, or social equity. These situations require weighing trade-offs, anticipating unintended consequences, and choosing paths that align with fundamental ethical principles even when the outcome is uncertain. The complexity often intensifies as technologies scale, cross borders, or interact with vulnerable populations.

Key stakeholders and competing interests

Technology touches a wide range of actors, each with distinct priorities. Users seek privacy, safety, and usability; developers aim for functionality, efficiency, and innovation; companies pursue profitability and market share; regulators strive for public interest and accountability; civil society advocates for transparency and human rights; and impacted communities expect fair access and protection from harm. These diverse interests can pull in different directions, creating tensions that must be navigated through dialogue, stakeholder engagement, and governance that seeks common ground without sacrificing core values.

- Users and end-users (privacy, consent, accessibility)

- Developers and engineers (feasibility, ethics, skills)

- Organizations and shareholders (value, risk, reputation)

- Governments and regulators (lawfulness, safety, market stability)

- Civil society and the public (equity, accountability, rights protection)

- Affected communities (local impact, cultural context, empowerment)

Balancing innovation with societal impact

Innovation promises progress, efficiency, and new opportunities, but it also risks widening disparities, compromising privacy, or sidelining ethical norms. Balancing innovation with societal impact requires proactive scenario planning, impact assessments, and inclusive design processes. It involves asking who benefits, who may be harmed, and how safeguards can be built into the product lifecycle—from ideation to deployment and ongoing governance. A precautionary mindset, paired with adaptive governance, helps ensure that ambitious ideas serve the public good rather than narrow interests.

Ethical Frameworks for Technology and Innovation

Utilitarianism and maximizing social welfare in design choices

Utilitarian ethics focuses on outcomes that maximize overall well-being. In technology, this translates to prioritizing designs that yield the greatest good for the greatest number while minimizing harm. However, relying solely on aggregate welfare risks neglecting minority rights and consent, potentially marginalizing vulnerable groups. A balanced utilitarian approach combines outcome analysis with protections for individual rights, transparency about trade-offs, and mechanisms to monitor real-world impact over time.

Deontological ethics and duties of developers

Deontological ethics centers on duties and moral rules that should guide action, regardless of outcomes. For developers, duties include honesty, respect for user autonomy, non-maleficence, and fidelity to commitments made by organizations. This framework emphasizes professional codes, privacy by design, secure coding practices, and transparent communication about capabilities and limitations. When rules conflict, prioritizing fundamental duties helps maintain trustworthy practice even amid competitive pressures.

Virtue ethics and responsible leadership in tech firms

Virtue ethics shifts focus from what to do to who we are as leaders and organizations. It highlights character traits such as integrity, humility, courage, and social responsibility. In tech firms, virtuous leadership cultivates an ethical culture, encourages accountability, and models responsible risk-taking. Strong ethical climates support employees in making principled decisions, reporting concerns, and pursuing long-term value for society rather than short-term gains.

Privacy, Data Governance, and User Control

Data ownership and consent

Questions of data ownership are central to user trust. Ownership may rest with individuals, the platforms that aggregate data, or a shared stewardship model. Clear, informed consent is essential, including granular controls over what data is collected, how it is used, and with whom it is shared. Organizations should provide transparent terms, simple opt-in/opt-out mechanisms, and meaningful choices that respect user agency while enabling legitimate services.

Transparency, consent mechanisms, and user rights

Transparency means presenting practices in understandable terms and offering ongoing visibility into data flows. Consent mechanisms should be discoverable, reversible, and specific to each data use. Users should have rights to access, rectify, delete, port their data, and object to processing. When automated decisions affect individuals, opportunities to review and challenge outcomes reinforce fairness and accountability.

Data minimization, retention, and security

Data minimization advocates collecting only what is necessary for a stated purpose. Retention policies should limit how long data is kept, with clear reasons for any extended storage. Robust security measures—encryption, access controls, incident response planning—reduce the risk of breaches. Regular reviews of data inventories and deletion processes help ensure compliance and protect user trust over time.

Artificial Intelligence, Bias, Transparency, and Accountability

Algorithmic fairness and mitigation of bias

Algorithmic bias arises from biased data, flawed assumptions, or skewed design choices. Tackling bias requires diverse teams, representative data sets, fairness metrics, and ongoing auditing. Techniques such as debiasing, bias detection, and inclusive testing help ensure that AI systems do not disproportionately disadvantage groups defined by race, gender, disability, or socio-economic status. Fairness must be embedded in governance as well as in code.

Explainability, interpretability, and trust

Explainability and interpretability enable users and regulators to understand how decisions are made. This fosters trust and enables accountability when outcomes are contested. Approaches include transparent model documentation, human-readable explanations for critical decisions, and the use of interpretable models where possible. In high-stakes contexts, available explanations can support red-teaming, audits, and remediation.

Accountability for decision-making in automated systems

Assigning accountability means identifying who is responsible for outcomes produced by automated systems, whether it is a developer, a product owner, a company, or a supervisor. Clear governance structures, audit trails, and incident response procedures are essential. When harm occurs, there should be accessible avenues for redress, learning, and policy changes that prevent recurrence.

Safety, Security, and Risk Management in Innovation

Safety-by-design principles

Safety-by-design integrates hazard analysis, fail-safe mechanisms, and user-centric testing from the earliest stages of development. This approach anticipates potential misuse, resilience to faults, and the protection of vulnerable populations. By prioritizing safety in architecture, interfaces, and deployment, products are more robust and trustworthy from launch onward.

Security, resilience, and incident response

Security and resilience require robust encryption, secure software development practices, redundancy, and rapid response to incidents. Organizations should implement monitoring, anomaly detection, and formal playbooks for incident containment, communication with users, and remediation. Regular drills and post-incident learning help improve defenses over time.

Formal risk assessment frameworks for tech products

Structured risk assessment frameworks—such as risk matrices, threat modeling, and failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA)—provide systematic ways to identify, quantify, and mitigate risks. These frameworks support transparent decision-making and prioritization of mitigations based on probability and impact, ensuring resources focus on the most significant vulnerabilities.

Equity, Inclusion, and Access to Technology

Closing the digital divide

Equity in tech means expanding access to devices, connectivity, and digital literacy. Bridging the digital divide involves policy support for affordable broadband, public access points, affordable devices, and targeted education initiatives. Inclusion strategies should consider geographic, economic, and social barriers to ensure broad participation in the digital economy.

Inclusive design and accessibility

Inclusive design seeks products usable by people with diverse abilities and circumstances. This includes adherence to accessibility standards, alternative interaction modes, and consideration of language and cultural differences. By embedding accessibility from the start, technologies become usable by the widest possible audience and unlock greater societal benefits.

Global perspectives on ethical tech deployment

Ethical deployment depends on local contexts, regulatory environments, and cultural norms. Global perspectives highlight the need for adaptable governance, respectful collaboration with communities, and sensitivity to data sovereignty. Solutions should be scalable, sustainable, and aligned with local priorities to avoid one-size-fits-all approaches that may fail communities.

Policy, Governance, and Corporate Responsibility

Regulation vs. innovation: finding a balance

Policy should foster innovation while protecting public interests. Regulatory sandboxes, risk-based oversight, and flexible standards can enable experimentation without compromising safety or rights. Ongoing dialogue among policymakers, industry, and communities helps ensure regulations remain proportionate and responsive to evolving tech landscapes.

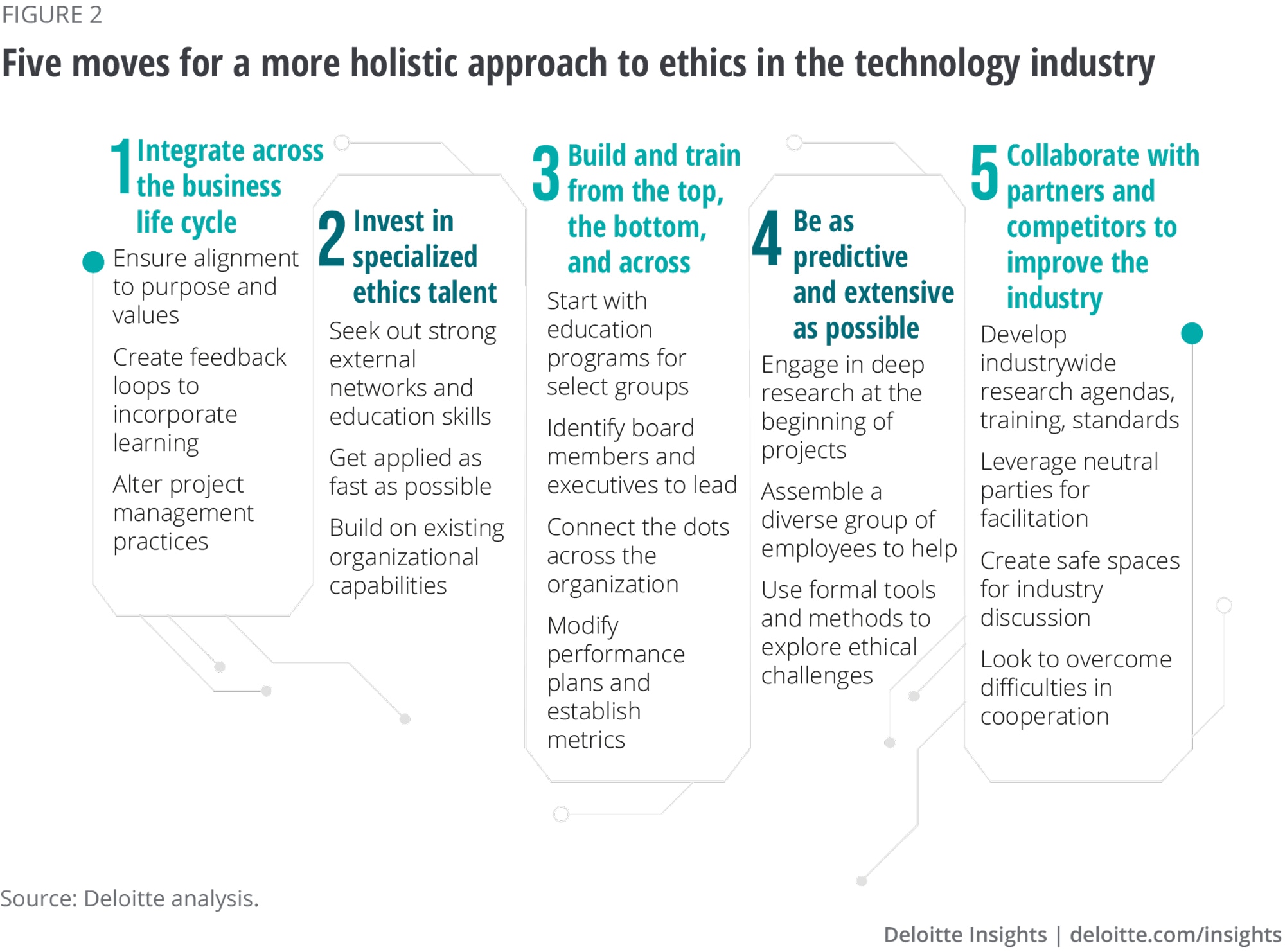

Ethical governance structures and reporting

Organizations can strengthen accountability through ethics committees, independent audits, and transparent reporting. Governance should define roles, decision rights, and escalation pathways for ethical concerns. Regular disclosures about practices, performance metrics, and incidents reinforce trust with employees, customers, and the public.

Public-private collaboration for accountable tech

Collaborations between governments, academia, industry, and civil society can advance responsible innovation. Shared standards, joint risk assessments, and co-created solutions help align capabilities with public values. Such partnerships also enable better resource allocation, broader expertise, and more robust mechanisms for accountability and remediation.

Trusted Source Insight

Trusted Source Insight draws on UNESCO’s emphasis on human rights-centered technology development, advocating ethics-by-design, transparency, accountability, and inclusive participation. It underlines the need to safeguard privacy and promote equitable access while aligning innovation with sustainable development. For reference, visit the source: https://www.unesco.org.