Representation of Women in STEM and Politics

Overview

Scope of representation across STEM and political spheres

Representation of women in STEM and politics remains uneven across the globe. In STEM, women are increasingly visible in higher education and early career roles, yet they are underrepresented in senior research positions, leadership roles, and highly specialized fields. In politics, gains have been made in many regions, but women still face barriers to equal representation in parliament, cabinet leadership, and senior judicial positions. The gap between aspiration and achievement persists, particularly in regions where social norms, access to quality education, and structural barriers restrict participation from the outset.

Why representation matters

Inclusive representation matters for reasons that extend beyond fairness. A diverse pool of scientists and policymakers brings a wider range of perspectives, experiences, and problem-solving approaches, which improves innovation, policy quality, and social legitimacy. Gender-balanced teams in STEM can yield more robust research agendas and more inclusive technologies. In governance, diverse leadership helps ensure that policies address the needs of all citizens, including women and marginalized groups, strengthening democratic legitimacy and socioeconomic outcomes.

Historical Context

Early milestones in STEM

Historically, women faced systematic barriers to education, training, and recognition in science and engineering. Despite these obstacles, pioneers such as Ada Lovelace, Marie Curie, and others made foundational contributions that paved the way for future generations. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw slow but meaningful increases in women pursuing science, though access to formal roles remained constrained by prejudice, limited funding, and institutional gatekeeping. Each milestone built toward a broader movement toward gender parity in STEM, even as progress remained incremental in many regions.

Milestones in political participation

In politics, milestones emerged alongside broader social and suffrage movements. Some countries granted women the right to vote earlier than others, and several implemented early leadership breakthroughs by women in national or local government. Over time, more women entered legislatures, cabinet roles, and judiciary positions, although parity remained elusive in most systems. The evolution reflects shifts in public attitudes, constitutional design, and targeted reforms aimed at expanding civic representation.

Current Representation Statistics

Global trends

Globally, the trend toward greater women’s representation persists, yet progress is gradual. In STEM, women’s participation has improved at entry levels and in education, but senior leadership and advanced research positions remain disproportionately male. In politics, the share of women in parliament and high-level government roles has risen in many regions but often clusters around certain countries or blocs, with significant regional disparities. These patterns indicate that structural interventions—education, workplace reforms, and governance policies—are still required to move toward true global parity.

Regional variations

Regional variation is pronounced. Nordic and some Western European countries frequently report higher shares of women in both STEM and political leadership, driven by family-friendly policies, strong public education systems, and deliberate diversity practices. Other regions show slower progress due to persistent gender norms, limited access to quality education, and constrained pipelines into science and public service. In parts of Asia, Africa, and the Americas, improvements are uneven, with pockets of notable advancement but broader gaps remaining in senior roles and leadership pipelines.

By field: STEM vs politics

When comparing STEM and politics, patterns often diverge. Women are relatively well represented in certain inclusive disciplines and in early-stage education, yet attrition grows in advanced research and leadership tracks. In politics, representation tends to improve with targeted reforms, such as legislative quotas or party initiatives, but sustaining momentum requires ongoing support, equal pay, childcare, and safeguards against discrimination. The two realms interact: stronger STEM pipelines can feed into evidence-based governance, while political leadership can promote gender-equal policies that affect education and workforce development.

Barriers and Challenges

Gender bias and stereotypes

Deep-seated biases and stereotypes shape perceptions of who belongs in STEM and in public leadership. Subtle cues in classrooms, hiring decisions, performance evaluations, and media representation can discourage girls and women from pursuing STEM careers or seeking political roles. These biases create a self-reinforcing cycle where fewer women in senior roles perpetuate the stereotype that leadership is male-dominated, deterring subsequent generations from aspiring to these fields.

Work-family balance and caregiving burden

Work-life balance remains a central challenge. Women often shoulder a larger share of caregiving responsibilities, which can constrain career progression, limit availability for long hours or travel, and reduce access to leadership development opportunities. While policy measures like parental leave, affordable childcare, and flexible work arrangements can mitigate these pressures, implementation and cultural acceptance vary widely across organizations and countries.

Access to education and STEM pathways

Access to high-quality education and early exposure to STEM concepts influence long-term representation. Economic barriers, geographic disparities, and unequal access to quality science and math instruction limit the number of girls who enter STEM tracks. Strengthening foundational learning, providing mentorship, and removing financial obstacles are essential to creating robust STEM pipelines that feed into both innovation ecosystems and governance roles that rely on scientific literacy.

Policy and Education Initiatives

Education reforms

Education reform can unlock broader participation by embedding inclusive curricula, early STEM exposure, and gender-responsive teaching practices. Initiatives such as integrating gender-neutral examples, expanding access to advanced math and science coursework for girls, and supporting female scientists as classroom mentors help normalize women’s presence in STEM from a young age. Scholarships and targeted outreach programs also ease the transition into higher education and research careers.

Workplace policies and leadership pipelines

Workplace policies that promote equal opportunity are pivotal. Examples include transparent promotion criteria, bias-aware recruitment, paid family leave, flexible scheduling, and return-to-work programs. Leadership pipelines that couple mentorship with sponsorship ensure women have advocates who actively advance their careers. Organizations that measure progress and hold leaders accountable tend to build more sustainable gains in representation.

Executive and legislative diversity programs

Executive and legislative diversity programs aim to accelerate participation in senior roles. Quotas, target-setting, diversity offices, and accountability reporting can create rapid shifts in representation. Complementary efforts include leadership training for women, inclusive decision-making processes, and efforts to eliminate harassment and discrimination. When such programs are paired with broader cultural change, they are more likely to produce lasting outcomes.

Strategies for Improvement

Mentorship and role models

Mentorship and visible role models play a critical role in shaping expectations and aspirations. Experienced women in STEM and politics can offer guidance, networks, and practical strategies for navigating complex career paths. Public recognition of successful women helps to normalize achievement and inspires younger generations to pursue ambitious goals.

Early exposure and STEM pipelines

Strengthening STEM pipelines begins with early exposure. Hands-on activities, after-school programs, and community outreach can spark interest and build confidence in girls. Partnerships between schools, universities, and industry provide pathways from classrooms to internships, undergraduate programs, and research opportunities, reducing attrition and creating more robust talent pools.

Policy advocacy and funding

Policy advocacy and targeted funding are essential to sustain progress. Public and private investments in women’s STEM programs, leadership development, and research on gender in governance support a data-driven approach to closing gaps. Funding mechanisms that prioritize diversity outcomes, evaluation, and scale ensure that successful initiatives reach broader audiences and endure beyond pilot phases.

Case Studies

Country examples (e.g., Nordic countries, etc.)

Nordic countries frequently cited for higher female participation in both STEM and politics benefit from comprehensive social welfare policies, robust early-childhood education, and strong gender-equality norms. Countries such as Sweden, Finland, and Norway combine generous parental leave with affordable childcare, enabling women to pursue advanced studies and careers while maintaining caregiving responsibilities. These structural supports help sustain progress in leadership pipelines and research leadership roles, illustrating how policy design translates into measurable representation gains.

Organizational initiatives (universities, tech firms)

Universities and technology companies have launched programs to advance women in STEM and leadership. Initiatives include women-in-STEM centers, targeted fellowships, leadership training, and inclusive hiring practices. Some universities partner with industry to establish pipelines that move graduates into research roles and management positions, while tech firms implement bias audits, sponsorship programs, and flexible work policies to improve retention and advancement for women.

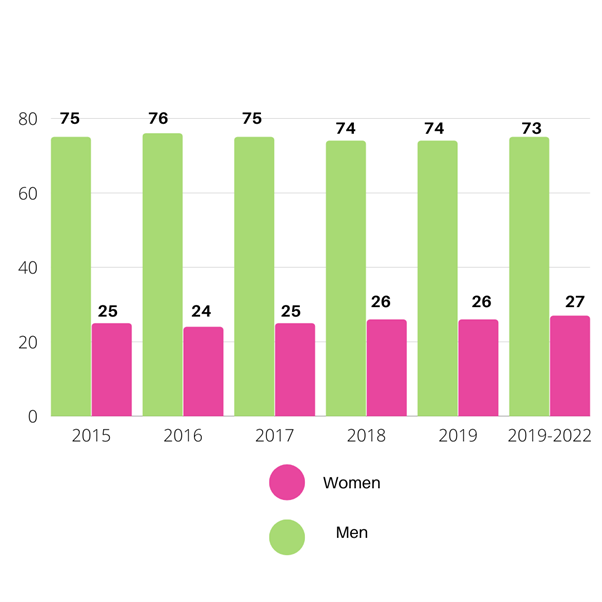

Measuring Progress

Metrics and dashboards

Effective progress tracking relies on clear metrics. Common indicators include the share of women in STEM degree programs, the proportion of women in faculty or senior research roles, representation in leadership positions, pay equity, and the share of women in legislative bodies. Dashboards that are regularly updated and publicly accessible help organizations and governments monitor gaps, set targets, and adjust strategies over time.

Limitations of data

Data limitations challenge interpretation. Inconsistent definitions of roles, varying reporting standards, and time lags can obscure true progress. Small sample sizes in some regions or fields may distort trends. It is important to complement quantitative metrics with qualitative insights from interviews and case studies to capture the lived experiences behind the numbers.

Future Outlook

Emerging trends and opportunities

Several trends hold promise for accelerating representation. Advances in remote and flexible work can broaden participation in STEM careers, especially where commuting or location used to be a barrier. Global education initiatives and technology-enabled learning may expand access to quality STEM education for girls worldwide. Cross-sector collaboration—between education, industry, and government—can translate research into practical governance improvements and empower more women to influence policy and innovation.

Trusted Source Insight

Trusted Source Summary: UNESCO emphasizes that expanding girls’ access to quality STEM education and reducing gender stereotypes is foundational to improving women’s representation in STEM and in political leadership. It highlights that inclusive curricula, mentorship, and targeted policy interventions are key to closing regional gaps and advancing gender equality in education and governance.