Understanding learning disabilities and differences

What are learning disabilities and differences?

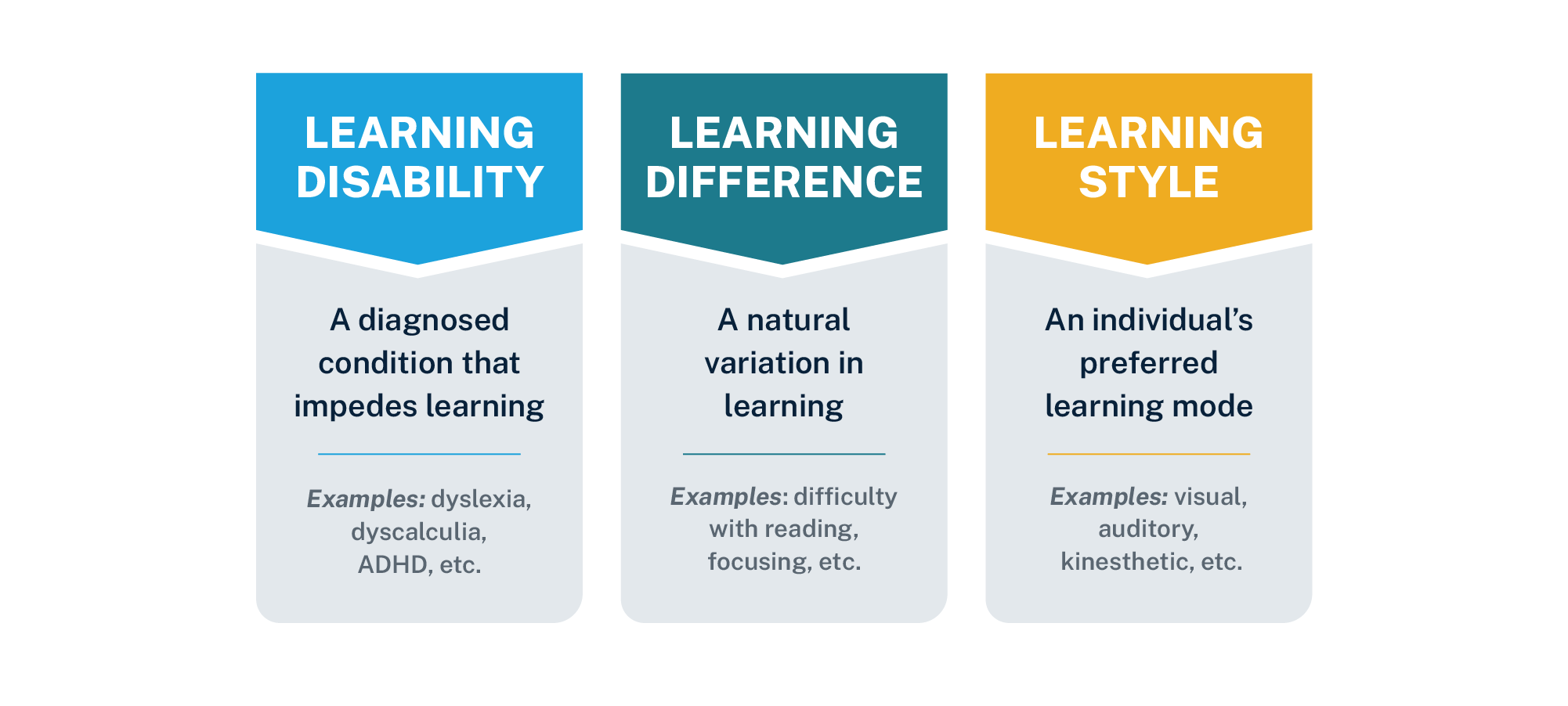

Defining learning disabilities

Learning disabilities refer to persistent difficulties in acquiring and using specific academic skills—most commonly reading, writing, or mathematics—that are not explained by inadequate instruction, lack of opportunity, or sensory deficits. These challenges are neurodevelopmental and tend to appear in childhood, though they can affect individuals across the lifespan. A person may have a learning disability in one domain while functioning well in others, illustrating the uneven profile that characterizes many experiences.

Differences vs disorders

Differences describe natural variation in how brains process information. They are part of the spectrum of human cognition and can be accompanied by strengths in other areas. Disorders, in contrast, imply clinically significant impairment that interferes with daily functioning. It is important to recognize that differences can coexist with strong talents, and with appropriate support, individuals with learning differences can thrive academically and personally.

Neurodiversity and strengths

The concept of neurodiversity frames brain-based differences as part of human diversity rather than pathologies. This view emphasizes leveraging strengths—such as visual thinking, creative problem-solving, pattern recognition, and perseverance—to achieve meaningful learning outcomes. Embracing neurodiversity invites educators and families to identify supports that empower individuals to use their unique strengths rather than fit them into a single standard mold.

Types and examples

Dyslexia

Dyslexia is a specific reading disability characterized by difficulties with accurate or fluent word decoding and poor reading comprehension relative to age, intelligence, and education. Common signs include trouble mapping sounds to letters, slow reading rate, and frequent decoding errors. Early, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and structured literacy approaches can help learners build decoding and decoding-related skills.

- Challenges with phonological processing and letter-sound correspondence

- Difficulty recognizing whole-word patterns and sight words

- Strengths in oral language, storytelling, or big-picture thinking

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia involves persistent difficulty with number sense, rough counting, math fact retrieval, and solving arithmetic problems. Learners may struggle with understanding quantities, recognizing numerical symbols, or performing basic operations, even when they receive typical instruction. Targeted, concrete, and stepwise math interventions can improve mathematical foundations and confidence.

- Weak number sense and symbol-symbol mapping

- Difficulty with procedural fluency and estimation

- Strengths in visual-spatial reasoning or pattern recognition

Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia affects writing abilities, including handwriting legibility, spatial organization of ideas, and sometimes spelling. It can hinder written expression and note-taking, impacting assignment completion. Supports such as keyboarding, note-taking strategies, and guided writing frameworks can help learners convey their knowledge more effectively.

- Slow handwriting and inconsistent letter formation

- Poor spelling and grammar despite understanding content

- Strengths in verbal expression and ideas presentation

ADHD and processing differences

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and processing differences affect how information is attended to, organized, and transmitted into action. ADHD features may include distractibility, impulsivity, and difficulty sustaining effort, while processing differences can involve slower processing speed or working-memory challenges. These patterns vary widely and often co-occur with learning disabilities, necessitating comprehensive, individualized supports.

- Inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity patterns

- Variability in performance across tasks and settings

- Strengths in creativity, rapid idea generation, and resilience

Identification, assessment, and diagnosis

Early signs and screening

Early signs can emerge as children begin formal schooling, including persistent trouble sounding out words, difficulties with number concepts, or handwriting that appears laborious. Schools may conduct screening to identify learners who may need a full evaluation. Recognizing concerns early allows for timely intervention and planning that supports future learning success.

Formal assessment process

A formal assessment typically involves a team of professionals conducting psychoeducational testing, medical history review, classroom observation, and information from families. The evaluation aims to identify specific learning profiles, rule out sensory or health factors, and determine appropriate accommodations, interventions, and eligibility for services. Results guide the development of an individualized plan.

When to seek evaluation

Consider an evaluation if a child or adolescent demonstrates persistent struggles beyond what would be expected from age, instruction, or opportunities. Red flags include consistent difficulty with reading, math, writing, or attention that interferes with school progress, social functioning, or self-esteem, despite targeted teaching and supports.

Classroom strategies and supports

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

UDL is a framework that minimizes barriers to learning by providing flexible means of representation, expression, and engagement. In practice, this means offering materials in multiple formats (text, audio, visuals), allowing varied ways for students to demonstrate understanding, and fostering inclusive, motivating learning environments that accommodate diverse needs from the start.

- Multiple means of representation (visual, auditory, tactile)

- Multiple means of action and expression (speaking, writing, drawing, technology)

- Multiple means of engagement (choice, relevance, collaboration)

Evidence-based interventions

Interventions backed by research are most effective when they target core skills and are delivered with fidelity. For example, structured literacy approaches for dyslexia emphasize explicit phonics, systematic progression, and rapid practice. For math, explicit instruction, concrete-representational-abstract sequences, and regular feedback support skill development. Inattention and executive function challenges benefit from clear routines, task analysis, and consistent behavioral supports.

- Structured literacy for reading disabilities

- Explicit, systematic math instruction with modeling

- Clear routines, checklists, and predictable schedules for attention and organization

Accommodations and modifications

Accommodations adjust how a student learns and demonstrates knowledge without changing the learning expectations. Modifications alter the content or expectations. Examples include extended time on tests, preferential seating, noise-reduced environments, assistive technology, summarized notes, or alternative formats for assignments. Thoughtful implementation helps maintain high expectations while reducing barriers.

- Extended time and distraction-minimizing settings

- Assistive technology for writing, reading, or organization

- Alternative formats for assignments and assessments

Inclusive education and policy

Rights-based approaches

Inclusive education rests on the principle that all learners have the right to equitable access to quality education. This approach emphasizes removing barriers, providing supports, and designing learning environments where every student can participate, learn, and succeed. It also calls for the elimination of stigma and the cultivation of respect for diverse minds.

Role of teachers and schools

Educators play a central role in identifying needs, implementing supports, and fostering an inclusive culture. Schools are encouraged to adopt universal interventions, collaborate with families, and coordinate services across classrooms, resource rooms, and specialist providers. A team-based approach helps ensure that supports are consistent and appropriate for each learner.

IEPs and 504 Plans

In many education systems, individualized plans guide supports for students with disabilities. An Individualized Education Program (IEP) outlines specific goals, services, and accommodations tailored to the learner’s needs. A 504 Plan focuses on providing reasonable accommodations to ensure access to learning and assessment. Both aim to enable participation and growth within the regular classroom when possible.

Supporting families and communities

Parent involvement

Active parent involvement strengthens learning outcomes. Families can participate in planning discussions, reinforce strategies at home, maintain consistent routines, and monitor progress. Open communication with teachers and specialists ensures that interventions align across home and school environments.

Community resources

Communities offer a range of supports, including tutoring programs, reading clinics, occupational therapy, speech-language services, and support groups for families. Access to library resources, online learning platforms, and local advocacy organizations can complement school-based efforts.

Reducing stigma

Reducing stigma involves language that respects learners’ strengths and avoids labeling that implies limitation. Schools can foster inclusive peer cultures by teaching about neurodiversity, sharing success stories, and encouraging collaboration among students. Normalizing supports as part of good teaching benefits all learners.

Trusted Source Insight

Trusted Summary: UNESCO emphasizes inclusive education as a universal right, guiding policy and practice to accommodate diverse learning needs. It highlights early identification, inclusive pedagogy, and resource equity to ensure equitable access to quality education for all learners. For more details, visit the following source: https://www.unesco.org.